On 6 April 1917 the United States of America made a formal declaration of war against Imperial Germany. At this point in World War I, due to the German policy of targeting all shipping in the war zone around Great Britain, a German victory was a distinct possibility. The submarine warfare perpetuated by the infamous U-Boats, along with the use of mines, had resulted in unsustainable British shipping losses.

In late March 1917 Rear-Admiral William Snowdon Sims, President of the US Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island, was sent to London to discuss the impact that the war at sea was having on British shipping. While still at sea en route to Liverpool, the United States declared war on Germany. In subsequent discussions with British naval authorities and others, Sims learned that, at the current rate of shipping losses, Britain would be out of supplies by the middle of the year, and this could compel the British to sue for peace with Imperial Germany. Sims urged American support for the British Navy, and this led to the decision to send destroyers to Queenstown.

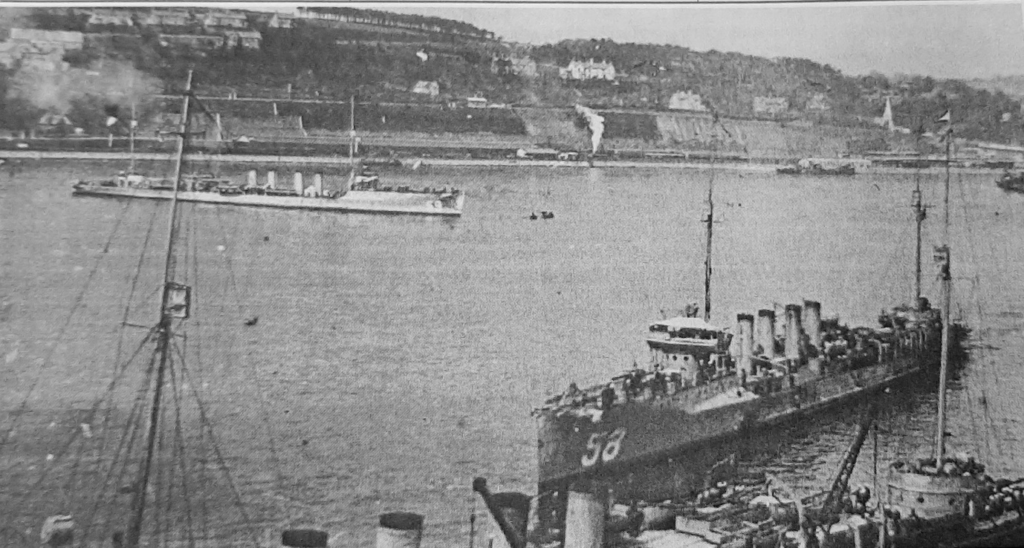

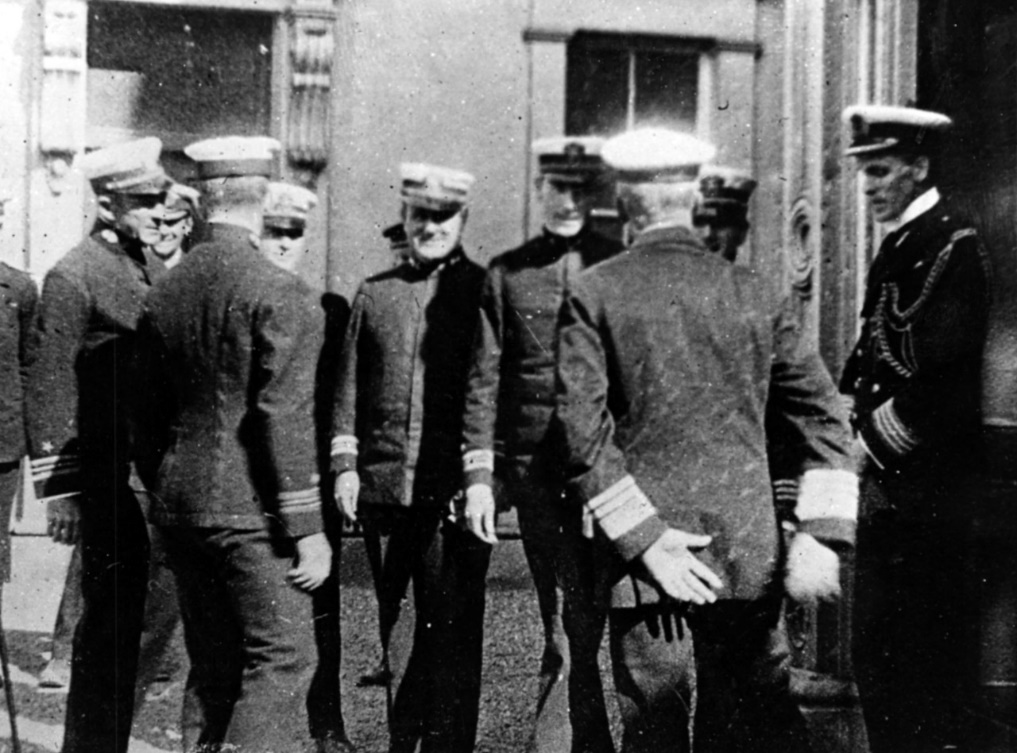

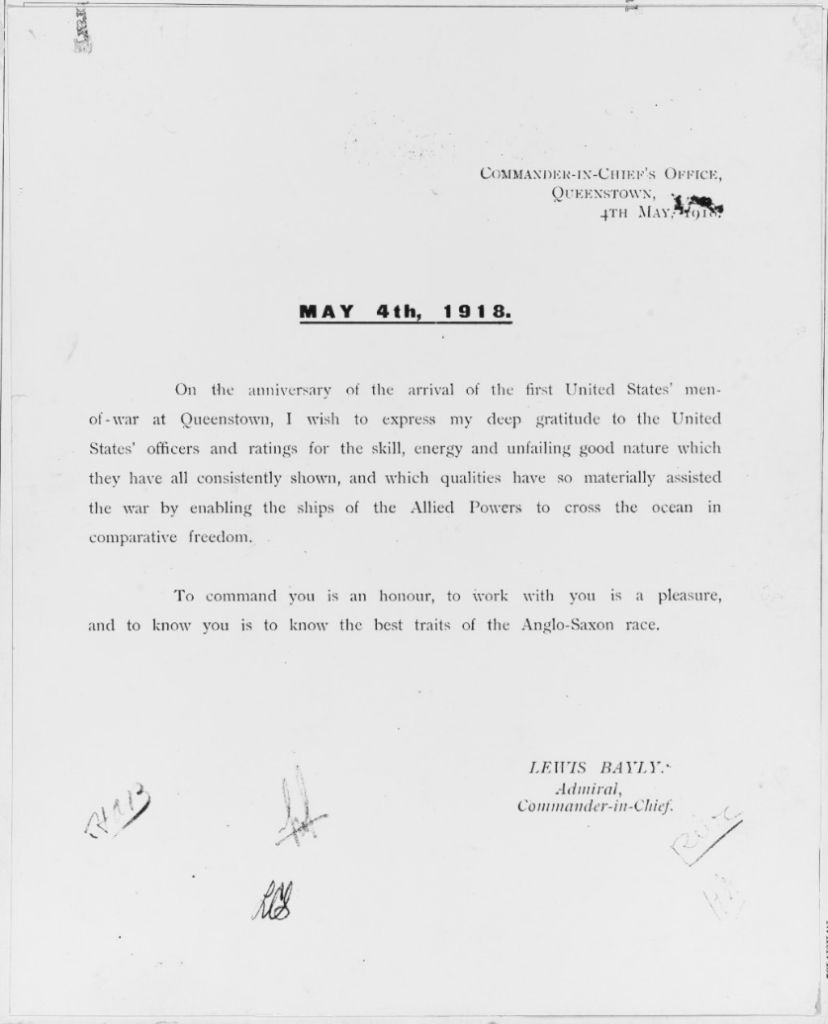

On 4 May 1917 a flotilla of six US Navy destroyers arrived off the Daunt Rock lightship in Cork Harbour. The six destroyers, Wadsworth, Conyngham, Porter, McDougal, Davis and Wainwright, under the overall command of Captain J.K. Taussig, were escorted into Queenstown by HMS Mary Rose. On arrival they were met by Sims (now promoted to vice-admiral and appointed commander of the US naval forces in Europe) and Vice-Admiral (later Admiral) Sir Lewis Bayly, RN, Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches.

For operational reasons the US naval force at Queenstown came under the command of the British Navy. Bayly, who was known for his abrasive manner, was asked by the British Admiralty to be ‘nice’ to the Americans. Following their first meeting, Sims described Bayly as being as rude as it was possible for one man to be to another. Despite this inauspicious start, the two men became very friendly and over the course of the war it appears that Bayly worked very well with the Americans, and they thought highly of him. On their arrival in Queenstown in May 1917, the skippers of the destroyers were Bayly’s dinner guests at Admiralty House, and as each new division of destroyers arrived, their captains were treated in the same way.

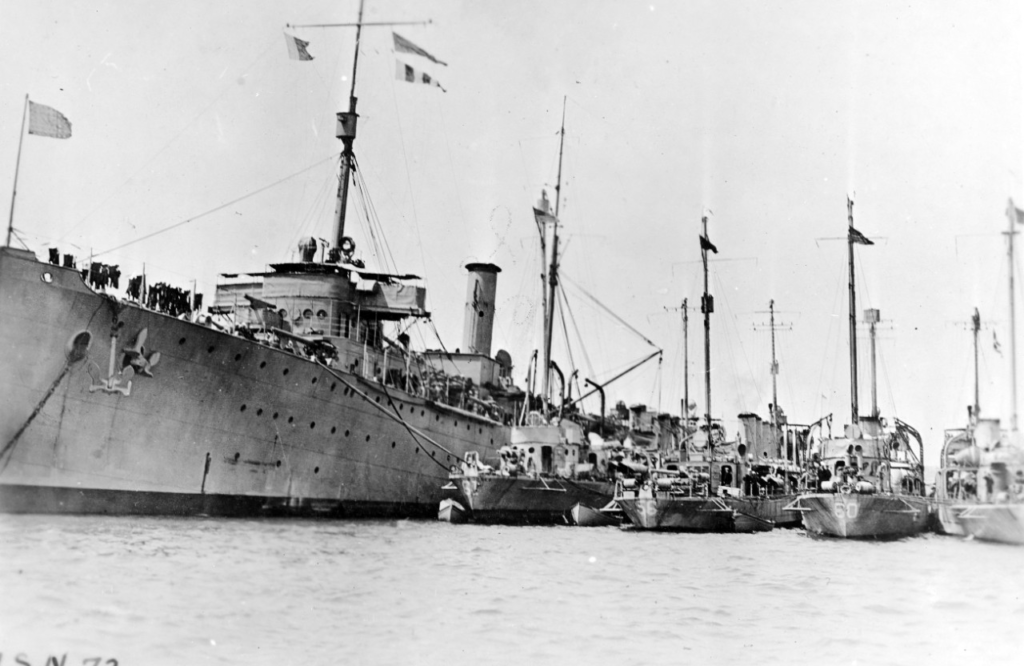

Between May 1917 and the Armistice, there were 92 US ships in the Queenstown command: two destroyer tenders, 47 destroyers, one submarine tender, seven submarines (based at Berehaven), one mystery ship (‘Q’ ship), 30 sub-chasers, one minelayer and three tugs. Naval seaplanes were based at several locations around Ireland including Aghada and Whiddy Island.

When the destroyers arrived in Cork Harbour, they carried single depth charges. They were quickly retro fitted with multiple depth charge racks and Thornycroft depth charge launchers. While the British Admiralty had some misgivings, the Americans pushed for the adoption of the convoy system to protect merchant shipping. Under this system the escorts of US destroyers and British sloops met incoming convoys up to 300 miles out in the western approaches in all weathers. They remained with them until they were close to their destinations, whereupon they would pick up outgoing convoys. The destroyers proved invaluable in counter-attacking submarines, which were targeting the convoys, and there is no doubt that the adoption of the convoy system was instrumental in defeating the German submarine campaign. The success of the system is borne out by the fact that in December 1917 roughly 350,000 tons of Allied shipping were lost, while in October 1918 only 112,000 tons were lost.

in the background.

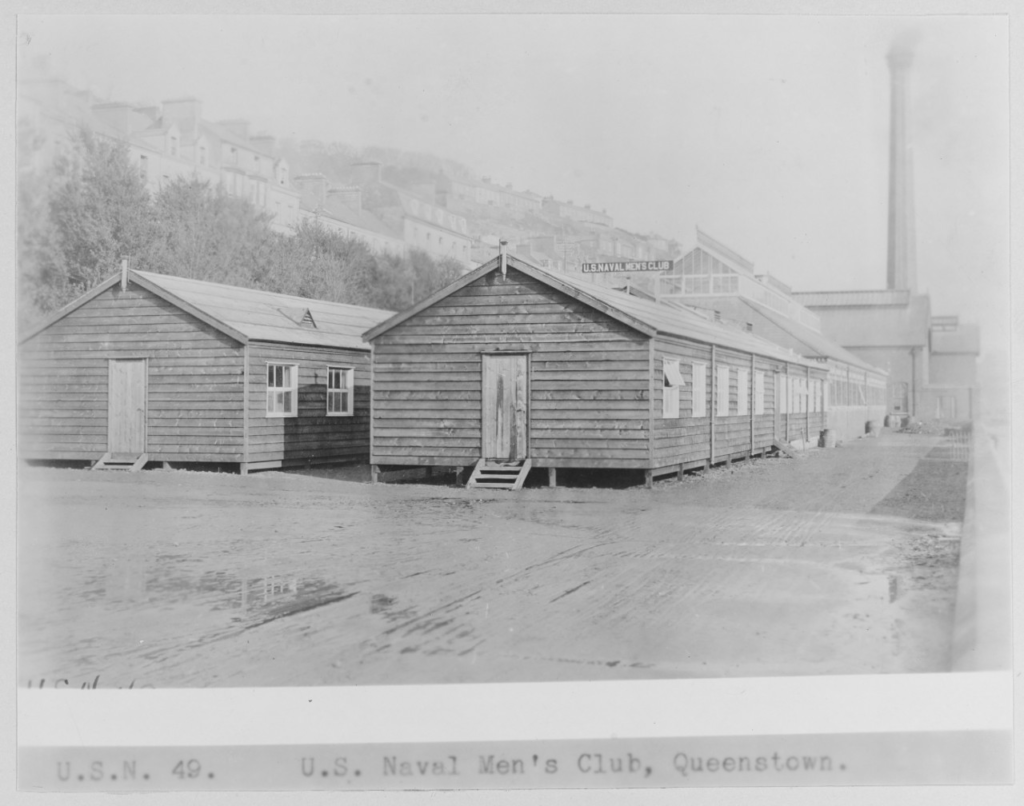

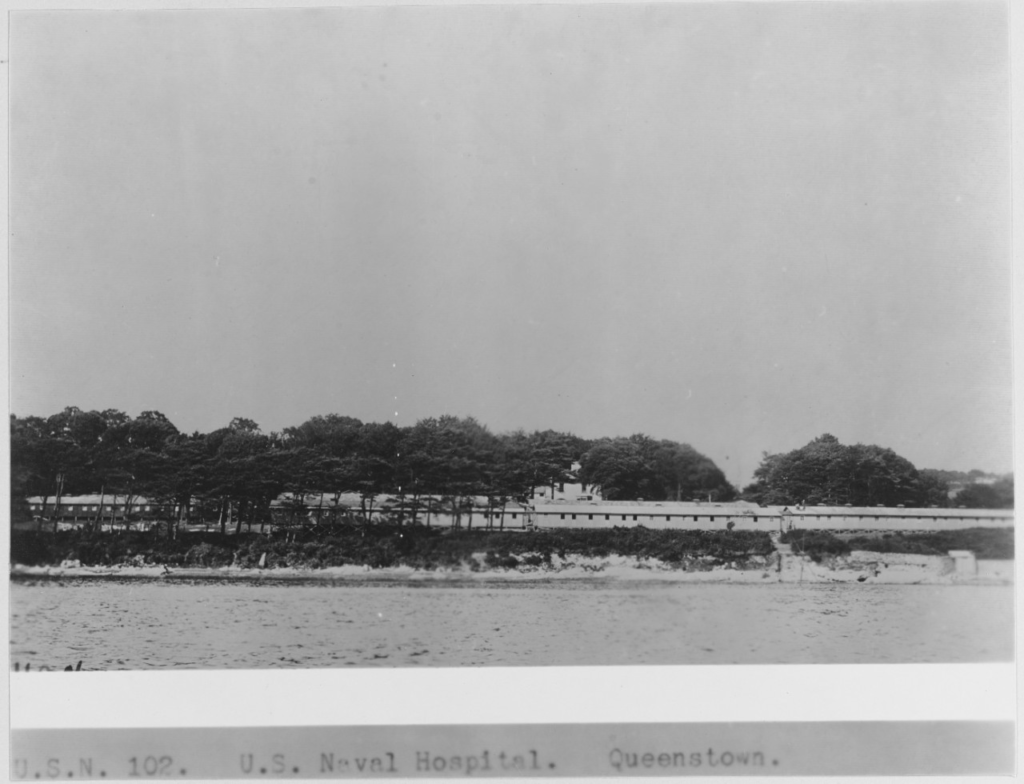

The existing naval facilities in Cork Harbour could not cope with the arrival of so many US ships and service men. An enormous pre-fabricated stores facility was constructed on a site running from the Deepwater Quay to Whitepoint. Recreation facilities were built, including a US servicemen’s club, which was located on the Bath’s Quay. The naval hospital on Haulbowline and the local hospital in Queenstown came under considerable pressure from US personnel presenting with various minor injuries and ailments. In May 1918 newspapers reported that American naval authorities had purchased a spacious dwelling house with a large area of land attached, situated not far from Queenstown, for the purpose of a naval hospital. Wooden dormitories, capable of accommodating up to 250 sick naval personnel, were built in sections in the United States and shipped to Ireland. The US Navy Base Hospital No. 4, as it was known, took up the entire grounds at Whitepoint House, and was staffed by US medical and nursing personnel. The existing pier at Whitepoint, which dates from the late 1870s/early 1880s, was used to ferry the sick and injured from ships to the hospital and as a result became known as the American pier.

Despite the cordial relationships between the officer class of both navies, there was considerable hostility between the enlisted ranks, but this was diminished by both sides having their own separate recreational facilities and favourite pubs ashore. In addition, there was rancour between US servicemen and local men, especially in Cork city. While naval personnel were initially permitted to visit the city, following several free-for-alls between sailors and local young men, an order was issued by Bayly prohibiting US servicemen below the rank of lieutenant from travelling to Cork or to within three miles of the city. While Sims believed that the clashes were the fault of Sinn Féin elements, it is more likely that local young men were annoyed by the amount of cash that was readily dispensed by naval personnel and the favourable impression that this made on the young women of Cork city. It is reckoned that the city suffered a loss of about £4,000 per week as a result of the ban. The Mayor of Cork appealed to Bayly to reverse the decision, but he refused on the basis that he could not be guaranteed that there would be no further trouble. The ban did not stop young women from the city taking the trains to Queenstown. Romances blossomed and marriages ensued. The presence of so many American sailors in Queenstown was also a draw for prostitutes, not only from Cork, but also from Dublin and London.

Following the signing of the Armistice in November 1918, the Americans began the process of withdrawing from Queenstown. In March 1919 Sims returned to the US. By May the hospital huts at Whitepoint were dismantled, although some were retained for use by the British forces. The last remaining ship, the Corsair, departed by June 1919. In November 1919 the US naval vessel Yankton arrived in Queenstown. The remains of 32 US naval personnel buried in the Old Church graveyard (Clonmel cemetery) were disinterred under the supervision of Dr Clarke Andrew and returned to the United States for reburial. In 1921 the US naval stores at the Deepwater Quay were demolished, except for one section, which was retained by the Cork Harbour Commissioners and used as a customs’ clearance shed for trans-Atlantic passengers until the 1950s.

Daire Brunicardi, who has written extensively on the naval history of Cork Harbour, observes in relation to the American navy’s departure from Queenstown, ‘their presence has left little lasting effect; it’s as if they were never there’. Perhaps the only lasting legacy in the town is the pier at Whitepoint, still referred to locally as ‘The American Pier’.

All photos: © Naval History and Heritage Command; www.history.navy.mil